"Supporting the

"Supporting the

foundations of the nation"

Fujita is a construction company with a history stretching back more than 100 years. Against a backdrop of in which more and more of the country's infrastructure is aging, they took on the task of removing Japan's first ever concrete dam.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Japan's first ever project to

remove a concrete dam

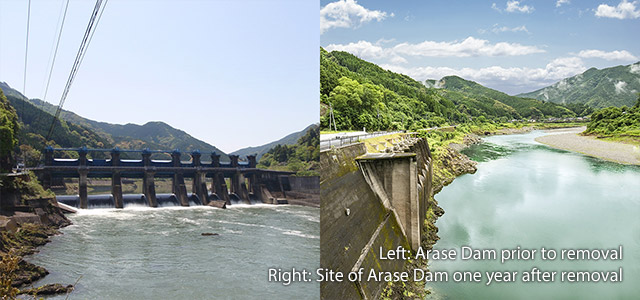

The clear-flowing Kuma River runs through southern Kumamoto Prefecture. Along its banks, can be seen fishermen, their fishing rods out in pursuit of the river's silver ayu sweetfish. This was once the site of the Arase Dam that utilized the river's abundant water to generate electric power. Completed in 1955, the dam played its part in economic development and river management for more than five decades until its water rights expired. The expiry meant the removal of the dam, starting in 2012, something that had never before been attempted in Japan for a concrete dam.

The project was commissioned by the Kumamoto Prefecture Enterprise Bureau and the work was contracted to a joint venture of Fujita Corporation and Nakayama Construction Inc. Toshimune Miyachi of Fujita was appointed as site manager. While his past experience encompassed a wide variety of different structures and construction work, including tunnels and bridges, overhead wires for the Shinkansen, and water storage and drainage systems, he had never previously worked on dams or demolition.

Arase Dam is 25.0m high and 210.8m along its crest. On first visiting the site and seeing the dam and its nine structural pillars, Miyachi was overwhelmed by the sight and left wondering whether removal was really feasible.

The pillars weren't the only challenge. The Kuma River's ayu fish make their way upstream each spring to spawn in the fall. This meant that river work could not start until early November after the hatchlings had made their way to the sea and could only continue through to mid-March. Moreover, work in the river's catchment was only permitted up to the end of February, meaning that only three and a half months were available in practice. It was on these terms that Japan's first ever large-scale concrete dam removal project got underway in April 2012.

Felling pillars as if they were trees

The removal of the Arase Dam was done as follows: (1) holes were made in the main body of the dam to lower the water level on the upstream side; (2) the steel gates located between the pillars were removed; (3) the spillway on the right bank that carried the main flow of the river was removed and the flow partially restored; and (4) the pillars and control bridge were demolished using blasting and heavy machinery and the main body of the dam removed to complete the job.

One difficulty was the blasting of the pillars. Because the concrete used in the original construction was reinforced with different material than what is used today, it was impossible to predict how it would respond to blasting. The specialist blasting company was hesitant to proceed. Miyachi's Fujita team and their joint venture partners consulted the literature to look for a safer alternative.

During that process, Miyachi came up with idea that perhaps they could cut the pillars down like trees. In a previous project, he had once used a chainsaw to cut down trees for a road as part of site preparation work. If a V-shaped incision was cut into the base of the pillars prior to blasting they should fall over as desired. He consulted with other companies that had done similar work in the past. A test blast was conducted on a bank-side pillar during year one of the removal project. While it didn't go the way they had planned, it did show the way forward to a successful conclusion.

In the winter of the second year, changes were made to the geometry of the V-shaped incision in which the blasting dynamite was positioned and preliminary work was done to cut the reinforcing in the body of the pillar to ensure it would collapse the right way. Finally, the day of the blast arrived. Watched over by a large audience that included people from the Enterprise Bureau, a television crew, and local residents, Miyachi commenced the countdown.

"5, 4, 3, 2, 1,... Blast!"

The explosion boomed out, dust billowed up, and the giant pillar fell gracefully to the ground. "In that moment, all my fretting and worrying was rewarded," said Miyachi. Hugs and handshakes followed with his jubilant team.

Nevertheless, their work was only just getting started. They continued making improvements with each pillar they brought down, making the process more reliable and precise and giving it their seal of approval: "This is the right way to do it."

Demolition of pillar by blasting

Site of pillar after removal

Building experience and passing it on

Civil engineering is said to be an empirical profession, with each site having its own unique terrain, geology, and weather conditions, better outcomes are achieved by building up experience and passing it on to those who follow. This applies to demolition as much as it does to construction. Miyachi did not rely on his own experience alone but rather brought in knowledge and expertise from both within Fujita and further afield.

One example is consideration for how to reduce vibration and noise when blasting near private residences or brick-walled railway tunnels. Based on advice from the company's engineering division, low-noise/low-vibration detonators, for example, are used in tunneling work near private residences when circumstances allow. The FON drilling used to make holes in the main body of the dam during the first year of the removal project was a technique of Fujita's that is used in tunneling where it helps reduce costs and get the work done more quickly. Similarly, the containment boom used on the river to prevent muddy water from flowing downstream is a practice normally used in harbor and river work. Likewise, to minimize any disruption to people who make their living from fishing, an effort was made to keep instances of the river water being muddied as short as possible, with work waiting for the water to clear again before proceeding.

As the work proceeded, the initial joint venture team of five started to dwindle as one or two people at a time moved on to other work. For the final two years, Miyachi stayed on his own in a lodging house and worked alongside the staff from the construction company. Miyachi came to call these workers, who applied themselves so diligently to the difficult task, his "family", adopting a strict attitude to safety compliance, saying, "I don't want my family to be hurt." He also put on a thank-you party at the end of each construction season, promising to see them all again next year.

In the final year, the sections where the dam met the river bank were left behind as "remnants" that would provide future generations with a reminder of history, with space also being cleared for a lookout. Six years after it had begun, the curtain finally came down on the project in March 2018 when this final task was complete.

Workers preparing for blasting

Civil engineering supports

the foundations of Japan

In the first summer of the Reiwa Era, Miyachi paid a return visit to the site where the Arase Dam once stood. The Kuma River has stretches of sand banks and rapids where the ayu fish go to spawn, and the transparency of its water has improved to the extent that you can now see the river bottom on some days. The population of diatoms (single-celled algae) on which the ayu feed has also risen, and the numbers of ayu and other wildlife are rising.

Gazing down on the river from the lookout, Miyachi recounts the early days of the project. "The time when I was still trying to figure out how to do the job was the toughest but it was also possibly the happiest," he laughs. Taking a fresh idea and successfully putting it into practice turns birth pangs into joy.

In doing so, he was helped along the way by many people. As he comments, "I learned from experience that, when trying to work something out for yourself, you lose sight of what is going on around you; whereas a word of advice from someone else can be enough to show the way forward." In putting Miyachi in charge of the project, the company gave him considerable discretion and watched out for him.

It was Miyachi's father who led to him choosing civil engineering, the field in which Fujita operates. When he was still in junior high school and uncertain of his future, his father told him that civil engineering is work that supports the foundations of Japan. This led him to go on first to study in that field, then to learn on the job, bringing him to where he is today. He still feels his father's words pushing him on. Miyachi pledges to keep working tirelessly to support the foundations of Japan and make a contribution to people and society through his job.

Toshimune Miyachi speaking against the backdrop of Kuma River

* The information in this article was current as of August 2019.

-

"A Free Hand to Design a New World of Luxury Houses"

"A Free Hand to Design a New World of Luxury Houses"

-

"The next mission in construction business"

"The next mission in construction business"

-

"An Athlete’s Flying Start to His Second Life"

"An Athlete’s Flying Start to His Second Life"

-

"Tackling the Challenges of Carbon Neutrality"

"Tackling the Challenges of Carbon Neutrality"

-

"Building Close Relationships with Our Customers"

"Building Close Relationships with Our Customers"

-

"Transforming the Construction Sector with DX"

"Transforming the Construction Sector with DX"

-

"Bringing Ever-More Joy to Travel in Japan"

"Bringing Ever-More Joy to Travel in Japan"

-

"Regeneration" Arises from New Construction

"Regeneration" Arises from New Construction

-

"An Enduring Spirit of Hospitality"

"An Enduring Spirit of Hospitality"

-

"Collaborating with 16 creators invited from around the world"

"Collaborating with 16 creators invited from around the world"

-

"Passing Down Hometown to Future Generations with Renewable Energy"

"Passing Down Hometown to Future Generations with Renewable Energy"

-

"The twenty-first century will be wind, solar, and hydro"

"The twenty-first century will be wind, solar, and hydro"

-

"Be a Pioneer in the Design Revolution"

"Be a Pioneer in the Design Revolution"

-

"Building better places to live through partnership between the public and private sectors"

"Building better places to live through partnership between the public and private sectors"

-

"Supporting the foundations of the nation"

"Supporting the foundations of the nation"

-

"Continuing to work the rest of life"

"Continuing to work the rest of life"

-

"Doing our best to support post-disaster reconstruction"

"Doing our best to support post-disaster reconstruction"

-

"Defying common wisdom in housing construction"

"Defying common wisdom in housing construction"

-

"Develop the American market!"

"Develop the American market!"

-

"Exporting Japanese industrial parks"

"Exporting Japanese industrial parks"

-

"Industrializing agriculture"

"Industrializing agriculture"